During my sophomore year of high school, I participated in the People to People Student Ambassador Program which culminated in a three week trip to Europe. Along with approximately 20 other high school students from across the state of Utah, I traveled wide-eyed through the countries of Italy, Austria, Switzerland, and France. Highlights of the trip included the city of Rome, Italian pizza, learning to ride a bike along the tree-lined streets of Vienna (yes, I was 16 – that’s another story for another post), purchasing illegally recorded techno music at a shop in Switzerland, admiring the Mona Lisa in person, and discovering the Frank Popp Ensemble on MTV France.

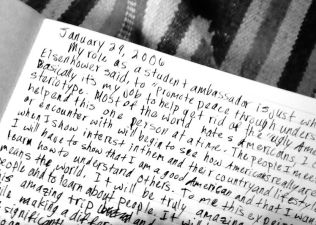

Prior to the trip, we completed fundraising projects and attended informational meetings aimed at teaching us to be conscientious travelers. Here is the first entry in my journal reflecting on the opportunity to travel: “(1/26/2006) My role as a student ambassador is just what (President) Eisenhower said, to ‘promote peace through understanding.’ Basically, it’s my job to help get rid of the ‘ugly American’ stereotype. Most of the world hates Americans, I can help end this one person at a time. The people I meet or encounter with will begin to see how Americans really are when I show interest in them and their country and lifestyle. … To me, this experience means the world. It will be truly amazing. I love to meet people and to learn about people. It will be so cool to go on this amazing trip and see so many beautiful things while making a difference. … I know I’m a lot more than a simple tourist. I’m making a difference, that’s really important to me.”

Whoa! Talk about being an idealist! And being totally self-centered (“It’s my job …”)! This might warrant a brief explanation. The program was created by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, apparently with the romantic goal of counteracting cultural misunderstandings that lead to international conflict. The logic follows what travel writer Rick Steves terms Travel as a Political Act: “Rather than accentuate the difference between “us” and “them,” I believe travel should bring us together.” So we were teenagers being inundated with Eisenhower’s dream of “peace through understanding” (even though we did not yet have a full grasp of world history or our place in the world); I’m going to say that’s why this theme came across so heavily in my writing.

Of course, I was still a teenager – a boy-crazed one at that. Consider another entry from my travel journal: “(7/2/2006) … We also went to Versailles. It was a huge castle (sic). I was really impressed by it. Everything was beautiful. There were hot Asian guys there and they asked to take a picture with me. It was so funny, I laughed a lot and then we got a picture. Today was full of laughter.” My trip to Europe certainly broadened my own horizons – I experienced great art and culture and friendship and I explored the inner boundaries of myself; in that sense, it was the essence of a coming of age adventure. But I had little interaction with the people whose countries we traversed in a giant, gas guzzling bus and apparently had dreams of Taco Bell throughout the trip – it’d be hard to say the experience counteracted damaging stereotypes that lead to international conflict on either side of the isle.

If my little travel journal had been published it might also epitomize writer Debbie Lisle’s central complaint in her book The Global Politics of Contemporary Travel Writing: “Too many travel writers remain unaware of how their work contributes to and encourages the prevailing discursive hegemonies at work in global politics.” In my journal, 16-year-old me is practically regurgitating the limitting rhetoric Americans are fed by mainstream news and politicians about “the world” hating us for our “freedom.” There’s no awareness of the complexities of global interaction or what role travelers can play. Likewise, I wouldn’t fare too well on David Spurr’s checklist for a discourse of resistance: in his book Rhetoric of Empire he says discourse that resists power imbalance constructively deals with problems of language, representation, interest, and other voices. Is it bad that my travel journal didn’t succeed in this regard? No, I was 16 years old and in Europe for the first time!

But would it be wrong if I continued this presentation now? Yes. As I consider my future as a traveler and travel writer, I don’t necessarily want to abandon my youthful optimism for “peace through understanding;” however, I do want to move far beyond this optimism into a place of true understanding, that’s focused not on teaching those Europeans to love Americans, but on teaching myself to love Europeans (and all “foreign” groups I encounter when traveling). In describing his reason for traveling to Iran, Rick Steves says in this YouTube video “I believe it makes sense to know people before you bomb them.” But as Steves’ goes on to describe potential errors of translation between the United States and Iran, I can’t help but think: if we knew them, maybe we wouldn’t need to “bomb them.” Maybe understanding, does in the long run, promote peace.

Chances are slim that I’ll be returning to Europe (or traveling outside the country at all) any time soon, and that’s okay. Lucky for me, I literally live next to one of the world’s top tourist destinations: Yellowstone National Park. In the summer months, the wait time at local restaurants naturally grows longer. Last summer, to avoid starving to frustration at Our Place (a local breakfast diner), my boyfriend and I agreed to sit with a couple from Denmark. They were traveling the states on a route that had taken them from Las Vegas to Cody, WY. Next stop: Yellowstone. Over several giant plates of pancakes, we experienced real connection (and discussed the importance of purchasing bear spray before entering Yellowstone). It wasn’t me laughing at a tourist in another country, but all of us, speaking in broken bits of language and relying on hand gestures to communicate, laughing together at the observations this couple had made regarding their vastly different American destinations. Experiences like this can be common in Cody, WY, and I try not to shy away from them.